Rule #23: Work for the Common Good

Strong Point’s Leadership Rule #23: Work for the Common Good

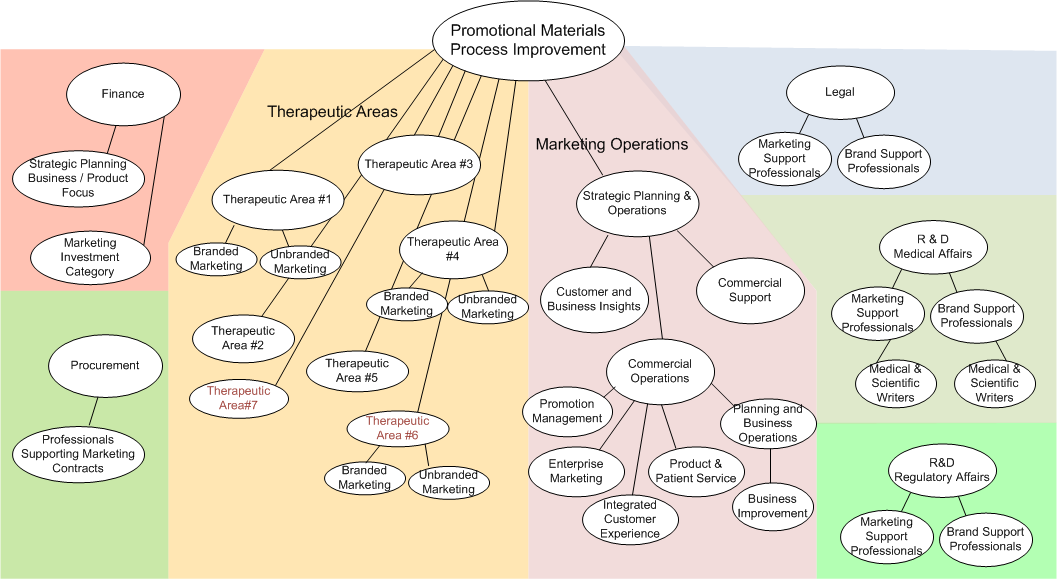

Business Transformation work requires Strong Point Solution Teams to understand a customer’s business function and purpose. They must also deeply understand the people behind that purpose. At the beginning of each engagement, it is Strong Point’s best practice to define and draw a stakeholder map, like the one illustrated below, which details the people and groups and their interconnectedness in organizing and executing important changes in culture and operations. We ask of and about stakeholders: Who are they? What do they care about? What role do they play in the proposed changes and the combined strength of the organization? and How does the planned change, affect them?

Strong Point uses a “Three I’s” approach to Stakeholder Management. We help clients make big, global changes more seamlessly and smoothly by breaking those changes into Incremental and Iterative actions and steps that are Individually Focused on specific stakeholder groups. The Three I’s approach is part of Strong Point’s Transformation Methodology. Strong Point Solution Teams work hard to integrate an important tenant of adult learning into their work: make changes relatable and specific to job functions.

Indeed, almost all effective and recognized Change Management theorists and experts like John Kotter and Daryl Connor recommend detailed and explicit stakeholder identification and management. Yet coined phrases like “What’s In For Me?” or WIIFM, or “That’s not my focus right now,” or “I’m not sure how that fits into my plan” are also very common responses to essential changes in active behaviors or functions. We as leaders and professionals are not all that inclined to help each other, never mind listen to each other, when we’re driven by constant demands and pressed for significant deliverables at the end of every workday or week.

In my work life through Strong Point engagements focused on Change Management and Business Transformation, I’ve never really felt quite comfortable with the “What’s in it for me?” mantra held up and chanted by change strategists. Even as I deeply and meaningfully agree that business transformations need to be stakeholder specific to optimize productivity and effort, I still feel that the second edge of that double-edge global/local, organization/individual sword cuts much deeper into the flesh of “why should I care?” than it does into scarred-over ways of working for the sake of future growth. A hard edge and angst persist in the psyche of individuals and teams participating in transformation efforts that leaves people wounded in the process of changing and growing.

We all know that change is hard. A lifelong friend always says with a chuckle, “if work were pleasant, they would call it fun and not work.” As I mapped out in Strong Point’s Leadership Rule #19: Live It to Learn It, the process of change mirrors Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ five stages of death and dying which are: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. The Intel colleagues of my early career days would say that change and growth bring out all the “FUDs” in people: Fears, Uncertainties and Doubts. Change is sometimes ugly, prickly work. It’s often uglier and more injurious than it needs to be.

Since reaching consensus and collective agreement is so vital to the process of changing how we work together and move forward, I hold the belief that leaders need to work toward the common good. Thus, Strong Point’s Leadership Rule #23: Work for the Common Good.

The African Proverb floats to the top of the thoughts in my mind:

“If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to far, go together.”

An African proverb

I often convey that Facilitation and Collaboration skills are in short supply and in ever-increasing demand in the new imperative for a complex matrix of companies, partner, vendors, suppliers to work together with greater depth, substance and shared interest than ever before envisioned. I often struggle with the passionate objection presented by customers, stakeholders, and even Strong Point Solution team members who claim that my methods are fruit-loops and pollyanna and not even possible to achieve intended outcomes. I get scoffed at for thinking that people even care about common good, let alone work to achieve it.Strong Point’s Leadership Rule #2: Caring is Key holds fast to the notion that leaders need to care about others: be they bosses, teams, subordinates, peers, partners or vendors. Strong Point’s Leadership Rule #5: It Matters Who. It Matters How reminds us that focus and dollars are spent five to one on Business and Technology vs. People.

While researching for this blog, I came across an awesome 2017 article in The Journal of Political Philosophy (Volume 00/ Number 00), called The Common Good: A Buck-Passing Account. The article was written by Eric Beerbohm of Harvard University and Ryan W. Davis of Brigham Young University. Wow. What a good read. The “hook” that got me reading the article with great delight was the notion of “Buck-Passing” and how it’s enacted in response to calls to work on behalf of the common good.

Public luminaries like American filmmaker, author, and political activist Michael Moore, and Sir John Edward Sulston, a British biologist and academic who won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with his colleagues Sydney Brenner and Robert Horvitz, hail the benefits and virtues of working toward common good:

“No decisions should ever be made without asking the question, is this for the common good? “

Michael Moore

“There’s always a tension between those who would like to garner wealth, and they contribute a lot to society. There’s also those who say, ‘I believe in the common good. I want that to be enlarged.’ They contribute a lot to society. The tension, the debate, between these two views is extremely important to our progress. “

John Sulston

With these thoughts in mind, the notion of “buck-passing” lingers. “Buck-Passing” resonates with me because the authors validate my experience that people often react to calls to work toward the common good, as masked manipulation or even coercion into “doing the right thing.”

Buck-Passing is the neutral term, Beerbohm and Davis use to describe what is often fierce backlash from stakeholders who resent being “guilted” into an action they perceive to be beneficial only to the party calling for the common good, and not necessarily for themselves or others. Humph.

Beerbohm and Davis then go on to highlight the two most common objections toward working for the common good:

It’s not always reasonable (too expensive, too time-consuming, too difficult, etc.)

It’s not existentially adequate. It just doesn’t make sense to everyone or a subset of participants working together to achieve a common goal.

Any of the Strong Point teammates, or professionals from one of the many customer, partner and vendor teams who’ve participated in our most recent work, could confirm the fact that there was a lot of fierce opposition, frustration, and buck-passing going on in most, if not all, of our collaborative working sessions.

The Beerbohm Davis article got me thinking about the collaboration Strong Point facilitates, and reflecting on why it’s so hard to work toward the common good. I found it useful, and I hope you will too, to contemplate some misunderstandings and myths about what “the Common Good” is and isn’t. Take a preview of some of the beliefs about common good debunked and decomposed by the authors listed below. I paraphrased some of their thoughts and added some of my own. See which thoughts resonate with you:

| The Authors’ (Beerbohm and Davis) Thoughts | My Reactions, Thoughts |

|---|---|

| The common good does not need to be valuable in and of itself; rather, it just has to have properties that provide a good reason to work together for participants. | An “aha” moment for me. The common good does not have to be “the right thing” or even righteous action (although it should be!). It can simply be a common goal! |

| Disparate parties have to have a good reason to work together. This can be a common good. | Strong Point examples of good reasons: – Advance Capabilities. – Combine the strengths of partners by integrating and synthesizing skills of disparate parties working together. – Share information and perspectives to promote common knowledge, challenges. |

| The term “buck-passing” is defined as avoiding the common good. | Love this! “buck-passing” could be a fun code word used to help teams, and stakeholders better collaborate and communicate. |

| There doesn’t have to be “buck-passing” regarding the common good, nor does one person or one party have to “guilt” the other party into working for the common good. | Whew. Keep the dignity in collaboration. |

| Working to guilt someone into working for the common good can engender backlash. | Backlash can come in the form of: – Stakeholders stonewalling/ sabotaging others. – Stakeholders just refusing to participate in collaboration(s). – Silent/passive-aggressive resentment and actions from teams/members. |

| Working for the common good, or right action, does not always promote a positive response or a “safe” state of affairs. | This is important to remember too. Even if the common good is the “right thing to do,” like re-doing significant amounts of work that produced unsuccessful outcomes, it doesn’t always feel good and is not devoid of conflict or frustration. |

| Our desires, intentions, and actions also have little to do with the common good. Working toward the common good really means that we’ve decided to work and act together. It’s about common agreement for a common cause. | Requesting to act for the common good does not have to be an emotional plea. It can be a fact-based goal and decision achieved through reflection and reason. Guilt or passion pleas need not be involved! |

| We don’t have to like working together to achieve a common good. We simply have to agree to work together toward it, even if unwillingly agree to disagree. | In so many engagements, the various stakeholders come from such different backgrounds and perspectives. Someone always feels like the activity is a waste of time or beneath his/her capabilities or unproductive relative to his/her individual goals. |

| Working for the common good doesn’t prevent you from also acting also on your own behalf and for your own good. | My advice is to not act on your own behalf while you are actively collaborating. Working for the common good requires sacrifice. Leaders often have to offer up precious resources like time and energy. |

| Working for the common good does not necessarily mean that you have to sacrifice or “lose something in the agreement” to work together. | Sometimes, in collaborative efforts, what feels like a sacrifice returns unseen benefits in learning, relationships, and professional equity that cannot be achieved by any other means! |

| Conversely, working for the common good does not mean that the common good or common agreement to work together is “good for everyone.” It can be that one person or one party gains absolutely nothing, and in fact, does lose something of value in the agreement. | I am thinking of many initiatives whereby new ways of working (ex: data capture activities) make one person’s role/job more burdensome and complex for the sake of higher-level decision maker’s ability to “see” key business trends and productive and/or unproductive operational patterns. |

| The common good is achieved through a deliberative and reflective process. People and Teams have to think about working together and choose/decide and agree to do so. | Oy! My reaction is that this decision and commitment is often a daily one! It’s hard work, to work toward the common good! |

| We can choose to act together for common and impersonal values or value systems. | Good examples are: for the convenience of the customer; the safety of the employee; for the overall well-being of the patient. |

This list was so comforting to me. It highlights so many of the challenges and struggles leaders experience when a variety of teams and stakeholders work together to achieve both individual and shared goals. The other thought I had in reading this list is that struggles to achieve common good exist in families, social communities and faith-based groups, too. Efforts to achieve a common good, teach leaders the discipline and skills needed to reach it. The list also reminds us to be vigilant in our efforts to pursue the common good.

A quote from Alan Dershowitz, famed civil liberties lawyer, and Harvard Law School professor, articulates the struggle we all face working toward common good:

“Good character consists of recognizing the selfishness that inheres in each of us and trying to balance it against the altruism to which we should all aspire. It is a difficult balance to strike, but no definition of goodness can be complete without it.”

Alan Dershowitz

Eric Beerbohm and Ryan W. Davis tell us that there are only three things needed to reach common good. Shared goals and agreement must be:

1. Distributively Neutral – which means shared goals, should be spread out neutrally and evenly among all the interested/ involved parties.

2. Non-Partisan – which means all parties have to have strong, good reasons for agreement around core concepts and principles to solve a common problem or achieve a common goal. They also have a common platform from which to disagree and make concessions so all parties can understand the overlapping benefits of working together.

3. Existentially Adequate – which means the common good has to make sense for everyone involved and have a good use for all the practitioners of the agreement, even if they don’t individually or collectively benefit from the agreement.

There are other things leaders need to keep in mind as they work toward reaching a common good.

One essential habit necessary for working toward common good is to check personal biases and perceptions. Debbie McGauran wrote a great article on January 2016, that’s posted on the Active Beat. It gives guidance for six ways leaders can work to combat internal mental filters. The shortlist is shown below. You can link to her article to learn more.

1. Beware of First Impressions |  |

Another good habit leaders can cultivate is “intellectual humility.” Amy Blaschka, a contributor to Forbes eMagazine, wrote an article on August 19th, 2019 to teach us all how to cultivate it.

Her short checklist to nurture intellectual humility includes questions like:

1. Do I think more like a soldier or a scout?

2. Would I rather be right, or would I rather be understood?

3. Do I solicit and seek out opposing views?

4. Do I enjoy the pleasant surprise of discovering I’m mistaken?

Strong Point’s Leadership methods are based on Servant Leadership. Underlying Strong Point’s methods is a belief that our God-given gifts, abilities, and talents are not to be used for our own good, but for the common good, and in service of others.

Strong Point’s Leadership Rule #23: Work for the Common Good